In Konkani, there are certain words whose plural forms are identical to their singular forms, differing only in vowel quality, with singular forms containing the ‘closed’ vowel and plural forms containing the ‘open’ vowel. For example: चोर [t͡soɾ] ‘thief’ (m.sg) ↔ चोर [t͡sɔɾ] ‘thieves’ (m.pl) & पोर [poɾ] ‘boy’ (m.sg) ↔ पोर [pɔɾ] ‘boys’ (m.pl). How did this come about? A diachronic linguistic process called umlaut is to blame!

What is Umlaut?

Umlaut is a type of assimilation, a linguistic process in which one sound changes to become more similar to a neighboring sound, either to ease pronunciation and/or to mark a semantic distinction. It often affects the nature of vowels in a language and is the reason English has forms like foot–feet and mouse–mice (we call this ‘Germanic Umlaut’).

Diachronic Konkani Umlaut

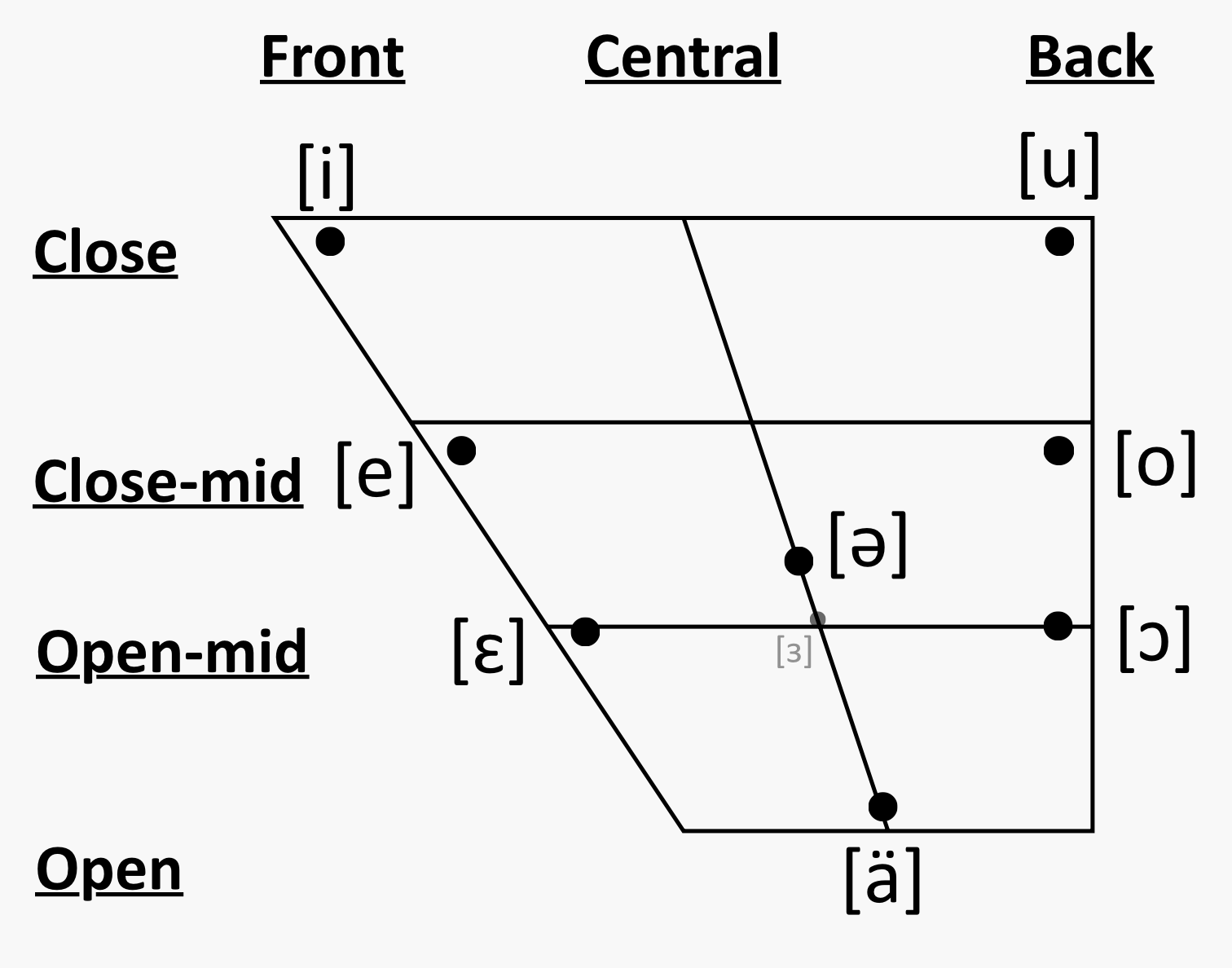

The Konkani umlaut can be defined as follows: When a word contained either the close-mid front [e] or close-mid back [o] followed by the close back [u] (or the close front [i]) in the next syllable, the preceding vowels remained unchanged. When the same vowels were followed by the mid central [ə], they were lowered (or opened) to open-mid [ɛ] and [ɔ] respectively.

{This could indicate that the Konkani ‘schwa’ is realized closer to the open-mid vowel [ɜ].}

Once the umlaut process was established and vowel qualities shifted, the distinction between close-mid & open-mid vowels persisted regardless of whether [u] or [ə] were retained or dropped.

Image- Vowels in Konkani

Let us look at some examples to understand how this happened-

‘Thief’ (m.sg)

चोरः → चोरो → चोरु → चोरु → चोर

ćōraḣ → ćōrō → coru → coru [t͡soɾu] → cor [t͡soɾ]

‘Thief’ (m.pl)

चोराः → चोरा → चोर → चोर → चोर

ćōrāḣ → ćōrā → cora → córa [t͡sɔɾə] → cór [t͡sɔɾ]

[Note how the final vowels dropped, yet the vowel changes caused by umlaut persist.]

[Stages are in the following order- Sanskrit (OIA) → Prakrit (Early MIA) → Apabhramsha (Late MIA) → Old-Konkani (Early NIA) → Konkani (NIA)]

Some other illustrative examples-

‘husband’ (m.sg)

गोहः → गोहो → +घोउ → घोवु → घोव

gōhaḣ → gōhō → +gʰou → gʰowu [gʱoʋu] → gʰow [gʱoʋ]

‘husbands’ (m.pl)

गोहाः → गोहा → +घोअ → घोव → घोव

gōhāḣ → gōhā → +gʰoa → gʰowa [gʱɔʋə] → gʰów [gʱɔʋ]

[Note- Some varieties of Konkani drop the final -w and have the [gʱo] vs [gʱɔ] contrast]

[+ = unattested or reconstructed]

‘brother-in-law’ (m.sg)

देवरः → देवरो → देअरु → देरु → देर

dēvaraḣ → dēvarō → dearu → deru [d̻eɾu] → der [d̻eɾ]

‘brothers-in-law’ (m.pl)

देवराः → देवरा → देअर → देर → देर

dēvarāḣ → dēvarā → deara → déra [d̻ɛɾə] → dér [d̻ɛɾ]

‘hair’ (m.sg)

केशः → केसो → केसु → केंसु → केंस

kēśaḣ → kēsō → kesu → kẽsu [kẽsu] → kẽs [kẽs]

‘hair’ (m.pl)

केशाः → केसा → केस → केंस → केंस

kēśāḣ → kēśā → kesa → kẽ́sa [kɛ̃sə] → kẽ́s [kɛ̃s]

‘boy’ (m.sg)

+पोतरः → पोअरो → +पोरु → पोरु → पोर

+pōtaraḣ → pōarō → +poru → poru [poɾu] → por [poɾ]

‘boys’ (m.pl)

+पोतराः → पोअरा → +पोर → पोर → पोर

+pōtarāḣ → pōarā → +pora → póra [pɔɾə] → pór [pɔɾ]

There are two special cases of this umlaut that create a semantic distinction (beyond simple pluralization). Interestingly, both examples represent fruit-tree pairs.

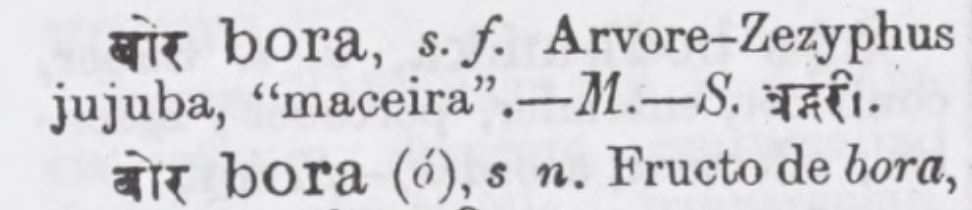

‘jujube tree’ (f.sg)

बदरी → +बअरी → +बोरि → बोरि → बोर

badarī → baarī → +bori → bori [boɾi] → bor [boɾ]

‘jujube fruit’ (n.sg) [Ziziphus jujuba]

बदरम् → बअरं → +बोर → बोर → बोर

bádaram → baaraṁ → +bora → bóra [bɔɾə] → bór [bɔɾ]

A snippet from Monsignor Sebastião Dalgado’s Konkani-Portuguese dictionary-

The next example is particularly intriguing, as it demonstrates the extension of this umlaut system even to two loanwords from Portuguese.

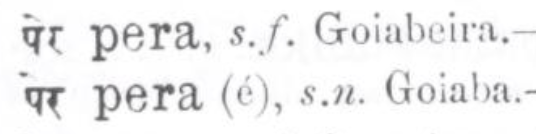

‘guava tree’ (f.sg)

Portuguese pereira /peɾɐjɾɐ ~ pɨɾɐjɾɐ/ → +पेरि peri [peɾi] → पेर per [peɾ]

‘guava fruit’ (n.sg) [Psidium guajava]

Portuguese pera /peɾɐ/ → +पेर péra [pɛɾə] → पेर pér [pɛɾ]

A Snippet Monsignor Sebastião Dalgado’s Konkani-Portuguese dictionary-

In Portuguese pera & pereira refer to the pear fruit & tree.

In Konkani it refers to the guava fruit & tree.

This umlaut likely occurred quite early in Konkani’s history, probably between the Apabhramsha stage and the Old Konkani stage (what could be termed the “proto-Konkani” period). I base this view on its presence in almost all varieties of Konkani, including those preserved by descendants of speakers who migrated southwards in the 16th and 17th centuries C.E., after Portuguese control over Goa had solidified.

Umlaut may also have been a key factor in the emergence of the open-mid vowels [ɛ] and [ɔ] in Konkani. It is possible that proto-Konkani +e and +o split into close-mid [e], [o] and open-mid [ɛ], [ɔ], subsequently spreading to different phonological environments within the language. However, it would be premature to draw a definitive conclusion on this point without further investigation.

Now you know why some words in Konkani have unique plural forms!